The core of care:

Essential Ingredients for the Development of Children

Home and Away from Home

Henry W. Maier, University of Washington, Seattle

In: Child Care Quarterly 8(3), Fall 1979

Adaptation of the first Abelour Lecture at the University of Strathcycle,

Glasgow, Scotland, October 27, 1977 and published in 1978 by the Abelour Trust,

Sterling, Scotland, Great Britain.

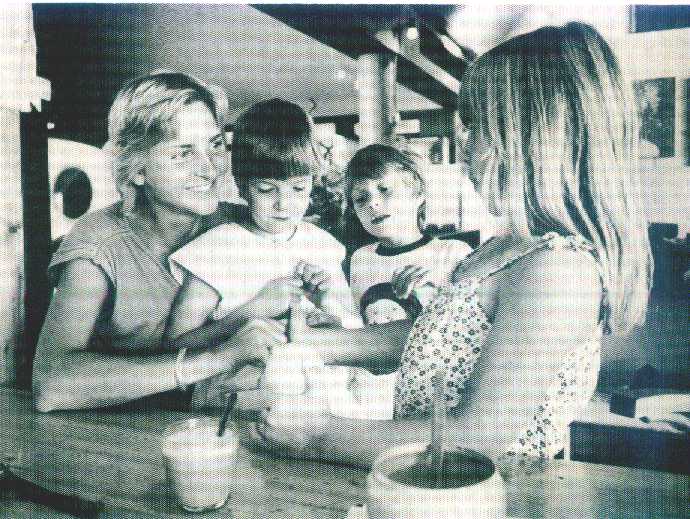

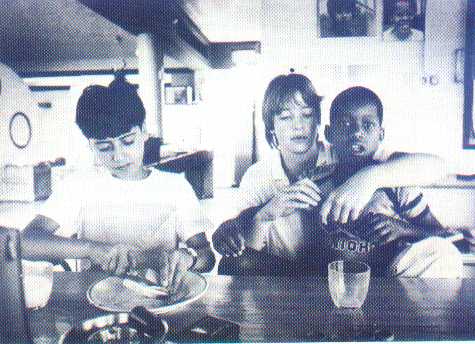

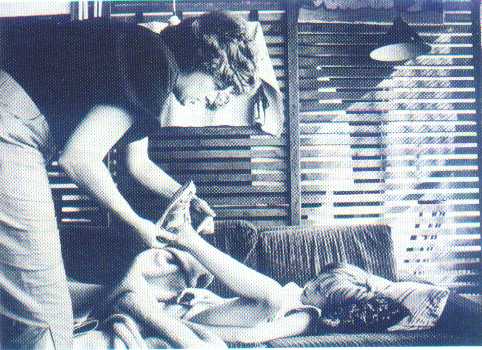

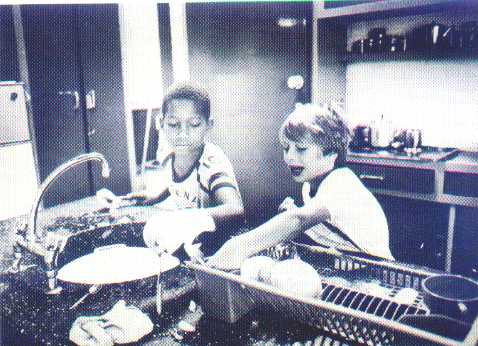

The illustrations are from the Dutch magazine Jeugd en

Samenleving that published a translation

in August 1983.

Abstract

Recent research findings in child development are applied to pertinent issues

in child care. Child care is presented as the provision of physical comfort

together with the experience of dependability and predictability. This composite

optimally enables the child to experience a very personal care and with it, the

feeling that he or she is special. Seven ingredients are outlined, and presented

with illustrative child caring activities, as the Core of Care.

Article

In the following pages I shall bring together some recent studies about child

development with a number of critical issues in child care. I shall try to

interweave these two spheres of learning, child development and child care.

Usually child development and child care interests are pursued as separate

concerns in disconnected research and teaching in departments far apart from

each other in our universities and in our field of practice, and more often than

not by persons unknown to each other. In actuality, a solid background knowledge

in child development offers basic directions for the care of children. In turn,

the everyday care activities provide rich data for the study of child

development.

In order for you, the reader, to become personally immersed in the ideas to

be presented, pause and think of an incident where you experienced nurturing

care. This would be a moment in your life when you had the sense of being the

one, and only one, who counted at that particular moment.

In reviewing such recollections of experiences of personal care, the

following components become apparent:

-

a sense of physical comfort;

-

a certainty that whatever care was experienced would continue or be

repeated beyond that instance of care and

-

most likely an involvement with a familiar and close caring person.

In short, at that moment there was a sense of special ness a sense of being

worthwhile, being fussed over and taken care off. These are our "whispered

moments of glory, our Camelots".*

* A line from the song on the

life and dreams of King Arthur - "Camelot".

These personal experiences of being nurtured reflect then some of the core

components of care. Although these components appear to be very simple, they are

more subtle and complicated when we try to implement them in the everyday care

of children and adolescents at home and away from home. These basic care

considerations apply in our work with children at all ages, regardless of

whether care is rendered in their own family or a foster home, in day-care,

temporary shelter, group, or residential.are.programs.

In would like to consider seven components of care. Each component is based

upon a compilation of long established child care wisdom. The most recent

findings in child development research shed light on the meaning these

discoveries have for child care. I tried to scan our knowledge of child

development as if to search for the "proper chemistry of care". Each

component is presented separately as a facet of care, but must always be viewed

and utilized in combination with the other six components. In totality, these

seven components constitute the core of care.

Component 1: Bodily Comfort

Bodily comfort as well as physical orientation, is basic to personal care.

This first component entails the kind of activities which we almost take for

granted. These actions are nevertheless, vital caring events. Consider the

caring act of straightening out a child's bed sheets in order that the child can

sleep in greater comfort, or sitting down on the floor with a child in order to

afford him or her a more relaxed bodily posture and more convenient eye levels.

One might say, as a child's bodily comforts are met, so does he or she feel

actually treated with care. Throughout life a sense of well being and care is

experienced when one's body is secure and free of somatic stress. With a sense

of physical well-being a person becomes more receptive and is, in fact, eager

for experiences beyond the immediate bodily demands. Physical sustenance and

comfort are basic for life and constitute one important measure of care.

In line with Component 1, physical comfort is strengthened by the involvement

of another person. It is this personal involvement, the investment of personal

energy which converts physical care into "caring care". The infant has

to be cradled into physical comfort. Newcomers to home, office, or a social

gathering need someone's personal presence in order to find a sense of physical

welcome and well-being. The same holds true in our everyday public life. For

example, the bus conductor's friendly overtures can render the automatically

opened door an easy and gratifying entry. In our child care practice, it occurs

to me what when I want to convey a "welcome" to an individual, my

words or smile might be less important than the energy I invest in the bodily

welcome I provide by means of a nod, touch, and comfortable physical

arrangements for the newcomers. Conversely, the negation of welcome, we know, is

readily accomplished by denial or restraining of "bodily rights".

Consider the studies of penal settings or concentration camps where extended

periods of standing, sitting, and sleeping in uncomfortable, or crowded

conditions quickly give the residents the understanding they are unwelcome,

worthless and isolated (Freedman, 1975; Helmreich, 1967; Radloff and Helmreich,

1968).

Physical Orientation

We have established then that concern for physical comfort is a prelude for

care. This concern is further conveyed in the way we deal with the individual's

personal space in their presence as well in their absence (Bakker, 1973).

In our everyday lives, household pets have their private spaces which are

duly respected. Do our children and adolescents also have the chance to establish

territory which is genuinely their own? In their rooms for daily activities, and

in their spaces for their belongings, for personal rest, retreat, and sleep,

this is especially true. Such private space has to be theirs "tax

free". In other words, this private space is theirs regardless of whether

their behavior has been acceptable or not. Their personal (private) corner, bed,

or other "mine only" place is undisputedly theirs as part of their

inalienable rights within the child care arena. Youngsters need to find this

evidence of the right to exist in difficult as well as in good moments. I am

reminded of instances when one child feels hurt that another has taken his

favored seat although other chairs are available and which appear to the casual

onlooker to be equally desirable. Studies of animal and human uses of space

clearly suggest to us that invasion of private space is felt as sharply as a

direct assault to the body (Bakker, 1973; Freedman, 1975). Robert Frost said it

well in his poem: "Good fences make good neighbors". This assertion

might also apply to children. They too want their territory known and respected.

Parenthetically, it is also significant that when children move from one

setting to another, from home to a residential setting or vice versa, that is,

from a familiar territory to a strange one, children require assistance in order

to make the unfamiliar familiar. Transitional objects - a much-loved blanket,

cushion, stuffed beast, toy, photo, or trinket - serve as a linkage transforming

a strange place into amore familiar surrounding (Winnicott, 1965).

It is inherent in the contemporary scene that each child care worker or other

helping persons serves also as a transition worker - as a person facilitating

client's transitions from one life situation to another. Clients need assistance

with entering, coping, and moving forward into their new situations. It follows

then that we need to guard against stripping individuals of their transitional

objects as they enter a hospital, correctional institution, day care center, or

other residential settings: continuous contacts with a previously supportive

person are not only a helping bridge, but are essential for the child as

transitional contacts.

Component 2: Differentiations

Individual differences inherently produce different interactions. A number of

recent challenging longitudinal studies suggest that from birth children are

quite different in temperament. These differences bring about distinctly varying

patterns of interactions with as well as by their char takers (Escalona, 1968;

Thomas, Chess and Birch, 1968; Thomas and Chess, 1977). Such findings suggest

that efforts to establish standardized expectations of behavior and

"consistent" handling within a group children is questionable. I

submit here that it is essential for caring persons to differentiate in the way

they respond to various children, even those with similar behaviors. To be

"consistent" is not necessarily a virtuous position. On the contrary,

it is neither an acceptable nor a desirable quality. To align our responses in

terms of the individual child is far more effective and natural and in no way a

deficient response.

If children do vary in temperament, then they logically secure for themselves

different life from their care givers (Brazelton, 1977; Lewis, 1974). More precisely,

children and caring adults discover each other as units of care and establish

their mutual mode of interaction. Most important, children's daily interactions

are more likely to vary on the basis of their differences in personal history,

sex, and social class (Thomas and Chess, 1977).

There are some children who seem to absorb rapidly what is going on around

them. They appear as if they were living radars. Although they strike us as

rather "inactive", they are in fact very active

"stimulus-scanners". They can deal with input over an extended time

while maintaining spatial distance from the events at hand. Thus they relate

most efficiently when they can interact with a predominantly visual situation.

In contrast we observe that other children require continuous physical contact

and bodily experience in order to feel involved. These children tend to have

manifold experiences within a short time. For them one interaction leads to

another. They are the "stimulus-bound" children - as if they were in

perpetual motion. Let us discuss the letter ones first, the more bodily active

youngsters. These "go-go" children are apt to enter immediately into

whatever is happening within their reach. Almost any stimuli becomes for then a

"call for action". Their own activities bring them continuously to new

and novel experiences.

When these "go-go" children were observed with their caregivers

(Escalona,

1968; Thomas, Chess and Birch, 1968; Schaffer and Emerson, 1964) a unique

process was observed. Spontaneously, caregivers tended to channel as well as to

limit their input. For example, while reading a story, the caregiver might read

with attention-stimulation, while at the same time holding her arm around the

child to reduce his/her bodily activities.

It is the child's temperament in interacting with his/her environment, as we

learned in the previously cited studies of Escalona, as well as of Thomas and

his associates, which shapes the quality of interaction, while it is the

caregivers' culture which defines the style of interaction.*

*Stimulus (S) and

Response (R) become interchangeable. One person's S is simultaneously the other

person's R, while the other person R becomes also the very same person's S.

The

caregiver, for instance makes the cultural choice between sponge or tub bath,

cold or warm water, but the nature of interaction within these boundaries is

found jointly. Readers may recall instances from their own contacts with babies

where quickly stimulated infants tend to be offered fewer toys because each

additional toy seems to detract from the previous one. Such children also have a

tendency to keep the caring adult on the scene of the child's actions. They

constantly involve themselves with the caregivers.

Living radars...

In contrast, in each of these studies we note that another large group of

children are active in another style. They are active "scanners".*

*Schaffer

called them the "non-cuddlers" in his Glasgow research project

(Schaffer and Emerson, 1964).

They tend to "case out" a situation

and maintain delibrate4 distance from others. Their caregivers in turn provide

them with bodily space or a buffer zone between child and adult. Simultaneously,

the caregiver recognizes the necessity to bring extra stimulation into the

child's activity. In infancy these children's cribs are filled with objects.

During feeding, bathing, and other forms of daily handling, caregivers tend to

introduce distinct stimulations by means of speech, touch, and visual stimuli in

order to evoke a mutual engagement (Escalona, 1968).

In child care settings we witness similar differences and handle them

according to variations in temperament. Some children come dashing to the dinner

table. They reach for the food while inquiring: "What's there to eat?"

The natural adult response the might be to focus on one thing at a time:

"Sit down!" "Sit!" "Sit down!" while

a pair of hands might be actively facilitating this anchoring process. In

contrast, in the instances of the "living radars", we would find such

boys and girls approaching the dinner table by giving it a complete survey

first. Typically they would focus on one item at a time, while still at some

distance from the table. The may call out: "She has my cup!" The

spontaneous adult response then might including offering several alternatives in

order to get the child fully into the scene. "Come sit down".

"Here is another cup just like the other one". "See here, your

soup is served". "Here is a place for you. Sit down!" All these

introductions of added stimuli occur from a distance, while the caregivers'

eyes, words, and perhaps their gestures are brought into play as intervening

anchoring mechanisms.

From longitudinal research we learn that both the "living radars"

children operating over distance, as well as their more intrusive counterparts,

the "go-go getters", develop satisfactorily. It seems that child and

caregivers tend to educate and find each other, to create, so to speak, the

proper fit. We learn from these studies that practical caring is neither an

activity to be delivered nor one to be developed out of manuals of house rules.

Rather, caring is a reciprocal interactive process of mutual adoption which

requires time and experience - and training for the care of special children.

Training will enable the caring person to discern which children require

immediate body contacts as part of close and intense personal interactions, and

which children can better achieve "closer" personal contact over

distance with a reliance upon eye and marginal body contacts. In short,

"different strokes for different blokes".

What does all this mean for the core of child caring? It suggests that the

care given and received requires and undisturbed extended periods of time

together in order to find a mutual fit. Parenthetically, this does not mean that

parents must stay at home at all times nor that the same child care personnel

should be continuously on their job. We know that children of working parents do

as well as children which the parent at home as so long as the caring parents,

in either situation, feel relatively free and are fully involved with their

children in the times spent together (Robinson et al., 1976). For child care

settings it might imply that it is most important to devise a program which

allows the child caring person full personal involvement when actually with the

children.

Component 3: Rhythmic Interactions

Rhythmicity is a vital feature of all human development. It is a

salient underlying force: the synchronization of child and caring adults. They

must somehow find their joint rhythm. (Brazelton, 1977; Byers, 1972; Condon,

1975; Lewis, 1974; Maier, 1978a; Schaffer, 1977, Pg. 63). Recent research

findings hint a possibility that basic units of rhythmic interactions make up

the "molecules of human behavior" (Byers, 1972, Condon, 1975). These

"molecules of human behavior" require the enmeshment* , the blending of a

individual's internal rhythmic with environmental rhythmic demands. It is this

subtle rhythmic involvement which determines the quality and possibly the

direction of interaction.

*The

descriptive term "enmeshment" I adapted from Schaffer's term

"social enmeshing" [Schaffer, 1977, Pg. 64-66])

Rhythmic experiences, such as rattling a rattle of repeatedly stroking one's

hair or beard, playing patty-cake or the shaking of hands, are all essential

ingredients of the experience of finding indicators of continuity. We note that Rhythmicity

is the hallmark of baby toys* as well as of real "togetherness" in later life events,

such as in group singing and dance, play or sexual activity.

*for instance, rattles, tops, music boxes with

repetitious tunes, lullabies, or action toys with built-in repetitious rhythmic

actions.

Rituals are a social counterpart to psychological

Rhythmicity. They

represent a confirmation of sound cultural practice. People experience a full

sense of togetherness in the carrying out of these practices* . In work with

children rituals assume special significance. By this I mean rituals of

significance to the child rather than routines which are neither rituals nor

training but purely for the purpose of achieving temporary order.

*for example,

the shaking of hands among some people, repeated bowing, or the rhythmic ritual

of kissing on both cheeks in other parts of the world.

What does Rhythmicity actually accomplish? Rhythmic activities seem to secure

for the individual the experience of repetition and continuity of repetition.

The actual experience of lasting repetition fosters a perception of permanency.

Rhythmic action contains the experience of repetition with the promise of

further repetition and hence the opportunity for experiencing predictability

(Maier, 1978b, Ch. 1).

When people get together, they attempt to locate joint rhythms in movements

such as the nodding of assent, or walking, laughing or even crying together.

They create a type of mutual sympathetic rhythm. In this connection, I

hypothesize that in play Rhythmicity is one of the salient features which

renders it a vital life experience. Notice for instance the rhythmic component

in playing ball, table tennis, or playing tag. These playful experiences provide

the possibility for becoming enmeshed in rhythmic encounters.

How is Rhythmicity applicable to the core of caring? I propose it is

essential that children have ample opportunities for both experiencing Rhythmicity

in their own activities and in their interactions with caring adults. When we

observe children engaged in repetitive, that is, rhythmic play such as

"aimlessly" bouncing or tossing of a ball, tapping out some rhythm on

the table, children chasing each other or bantering insults etc., we must

recognize that all these are far from time-wasting activities. Moreover, when

adults while caring for children can become part of the joint rhythm, they have

the possibility of finding themselves momentarily fully "in tune" with

the children. Children and adults share moments of moving ahead together.*

*Mike

A. West Sr., a social worker in Seattle, Washington, called to my attention the

fact that a different developmental levels children, adolescents, and adults are

more "in tune" with specific relevant musical rhythms. For

adolescents, regardless if it is within the jitterbug, twist, or hard rock era,

the rhythm remains alike for each variation of contemporary music.

Component 4: The Element of Predictability

The capacity is a measure of knowing and an essential ingredient of effective

learning. In other words, to know which things will happen in the immediate

feature lends a sense of order and power. It becomes a major breakthrough for a

youngster to discover that she/he can predict the outcome of her/his action. He

or she can make things happen.*

*Hy Resnick phrased such discovery aptly

"a shift from random to random less behavior"; that is, a move toward

controlled existence in an orderly world).

Child care activities must therefore offer continuous work with children in

such a way that they truly experience and cherish the meaning of their own

activities. It will be significant then for the caring person to mirror his/her

experience of the happening for the effectiveness of the behavior rather than as

a gauge of approval. The caring person might say, in sharing the events of the

child who performs somersaults as a guest arrives, "You got my full

attention all the way with that one. You really did it!"

Actually, we tend to use an approval quite easily with very young children.

With other children, however, we are less prone to do so. With this latter age

group we are apt to shift our involvements away from the doing and learning

directly; we tend to engage ourselves instead in regulating or evaluating. With

older children is is of equal importance to be constantly involved with a boy's

or girl's action and mastery. For instance, the youngster accomplishing a new

task requires recognition for the mastery rather than an evaluation in terms of

"good", "brave", or "industrious". Children

require feedback on their competence acquisition rather than another check off

on adults' list of approved conduct.

Component 5: Dependability

A sense of predictability heralds a sense of dependence (Maier, 1978b). The

sense of prediction assures an individual a sense of certainty. A sense of

certainty gives a person an assured feeling of dependence. As children come to

know and to predict their experiences with others, so will they depend upon

these persons. Moreover, these very experiences become significant encounters in

their own right. To be able depend upon dependence feels good! It assures the

child that she/he is not alone and that she/he can depend or rely upon support.

The feeling of dependence creates attachment and having attachments feels good,

too (Brazelton, et al., 1974; Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Maier, 1977). The caregiver

in turn also wants to be depended upon. Dependence feels good and is good for

both of them.

The experience of dependency is the basis for undependability

Dependency then, is natural and desirable - and basic to child care. The

continuous and very personal involvement in the caring process fosters a

dependence to the point that child and adult deeply care for each other. After

all, little people need big people and big people also have the need for others,

both big and small ones. In Brofenbrenner's terms, every child needs at least

one person who is really crazy about him or her (Bronfenbrenner, 1977, Pg. 3).

When a child feels that someone really believes in him (her) the child then

feels good about him/herself and eventually about other people. Curiously

enough, when persons experience secure dependence upon one another, they can in

fact function more independently as they feel assured of mutual attachment

(Maier, 1977). Secure dependence breeds clear independence and ultimately the

freedom for new dependence in new and more complex relationship systems (Maier,

1977)*. Recent studies on attachment experience have

made us aware that a lack of dependent experience creates greater havoc in a

child's development than prolonged dependence itself (Brunner, 1970; Maier,

1977, NICHHD, 1968).

* For a full discussion of the author's formulation of

dependence/independence oscillation see the essay Dependence and Independence

development Throughout the Human's Life Cycle: Implications for the Helping

Professions (Maier, 1977).

Component 6: Personalized Behavioral Training

Social capability rests upon personal attachment. The reader may have noted

that thus far there has been neither a reference to the maintenance of

discipline nor the training in self-management and manners. The reader could

easily wonder whether the writer cares all about children's behavior? (I do! In

fact, I care so much that I want the behavioral training to have the fullest

possible impact).

Children learn most readily those who have vital meaning for them. They turn

to the persons they have experienced ones to be counted on, namely those whom

the children perceive as on their side (Bronfenbrenner, 1970; Kessen, 1975;

Schaffer, 1977, Pg. 100). Children are most likely to follow the persons whose

ways of dealing with life issues are most akin to their own. The persons most

meaningful for their power, as well as the persons closest to the children's own

life situations, have the best chance for influencing the children's behavior.

(In addition to the primary caring persons, very frequently it is the slightly

older siblings and peers or the heroes in stories and TV, a few steps ahead in

their development, who represent the models and idols; and they may be almost of

equal importance to the central caring figures).

Concern with social training has been purposely introduced late in the

sequence of the seven components. It is essential to keep in mind that the most

potent behavioral training goes hand in hand with a sense of reciprocal

closeness and attachment. Effective acquisition of behavioral standards is a consequence

of dependability. When children and caring adults are in a close relationship,

effective child training really starts and the more complicated socialization

efforts can now take place.

It is important to recognize however, that both child and caring adult must

eventually go far beyond their mutual attachment to other spheres of life, where

children will be more and more independent of their care givers within new

spheres of dependencies. (Maier, 1977). In the child care settings, the children

continuous involvement with their lager community and with their own family or

future foster or group home setting is of utmost importance.

The core of care in and away from home has to be experienced in a series of

meaningful activities as children mature. While engaged with their caring

adults, children will periodically dip into emotional dependence upon these

caring persons, and this linkage will be both fundamental and freeing. In other

words, fostering self-management and enriching children's behavioral repertoires

are intimately linked with the formation of close relationship with the care

givers.

Stimulating the autonomy of the children

Component 7: Care for the Care Givers

Component 7, care for the care giver as the final ingredient, is fundamental

to the previous six. Care can only be received to the extent that the care

givers are personally prepared and ready to engage in these interactions. It is

inherent that the caretakers be nurtured themselves and experience sustained

caring support in order to transmit this quality of care to others.

Care givers are enriched or limited as agents of care according to the care

they receive. Are their activities in their role as givers supported by their

own personal caregivers, their primary groups, and their wider social

institutions? Are caregivers assured of their own physical comfort and ample

personal privacy in space and time, and are they provided chances for secure

support from others when the care giving becomes rough? Do they have access to

resources for doing what has to be done? In short, is there ample care for the

caring?

Concluding Comment

The essential message can probably best be summarized in the greeting which

nowadays is frequently heard among young adults. On leave-taking, they often

exchange two simple but powerful words: "Take care!" This phrase seems

to encapsulate a theme: true caring largely reflects the mutuality of care

received and care rendered. All of us, adults and children, need this exquisite

blend of affirmation.

References

Bakker, C.B. & Bakker-Rabdau,

M.K. No trespassing. San Francisco:

Chandler and Sharp, 1973.

Brazelton, T.B. Effects of maternal expectations on early infant behavior. In

S. Cohen & T.J. Comoskey (Eds.), Child Development. Itasco, Il:

Peacock, 1977, Pg. 44-52.

Brazelton, T.B. Berry, Kolowski & Main, M. The origins of reciprocity:

The early mother-infant interaction. In: M. Lewis & L.A. Rosenblum (Eds.), The

Effects of the infant on its caregiver. New York: Wiley 1974.

Bronfenbrenner, U. The fracturing of the American family. Washington

University Daily, October 5, 1977, Pg. 5 (Summary of a lecture). New York:

Russell Sage Foundation, 1970.

Bronfenbrenner, U. Two worlds of childhood. New York: Russell Sage

Foundation, 1970.

Brunner, J.S. Poverty and childhood. Detroit: Merrill Palmer, 1970.

Byers, P. From biological rhythm to cultural pattern: A study of minimal

units. New York, Columbia University, 1972. (Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation).

Condon, W. Speech make babies move. In R. Lewin (Ed.), Child Alive. New

York: Doubleday, 1975.

Escalona, S.K. The roots of individuality. Chicago:

Adline,

1968.

Freedman, J.L. Crowding and behavior. New York: Viking Press, 1975.

Helmreich, R.I. & Collin, B.E. Situational determinants of affiliative

reference under stress. Journal of personality and Social Psychology,

1967, 6, 79-85.

Kessen, W. (Ed.) Childhood in China. New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press, 1975.

Lewis, M & Rosenblum, L.A. (Eds.) The effects of the infant on its

caregiver. New York: Wiley, 1974.

Maier, H.W. Dependence and independence development throughout the human life

cycle: Implications for the helping professions. Seattle, WA: University of

Washington, 1979.

Maier, H.W. Piagetian principles applied to the beginning phase in

professional helping. In R. Weizmann, R. Brown, et al (Eds.) Piagetian theory

and the helping professions. Los Angeles: University Press, University of

Southern California, 1978(a), Ch. 1, Pg. 1-13.

Maier, H.W. Three theories of child development. (3rd Rev. Ed.), New

York: Harper and Row, 1978(b).

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Perspectives on

human deprivation: Biological, psychological and sociological. Washington

DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (DHEW), 1968.

Radloff, R & Helmreich, R.L. Group under stress: Psychological

research in selab II. New York: Appleton, Century, Crofts, 1968.

Robinson, H.B., Robinson, N.M.,

Wollins, M. et al Early Child care in the

United States of America. New York: Gordon and Breach, 1976.

Schaffer, H.R. Mothering. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,

1977.

Schaffer, H.R. & Emerson, P.E. The development of social attachments in

infancy. Monographs of Social Research in Child Development, 1964 (29)94.

Thomas, A. & Chess, S. Temperament and Development. New York:

Brunner/Mazel, 1977.

Thomas, A, Chess, S. & Birch,

H.G. Temperament and behavior disorders

in children. New York: New York University Press, 1968.

Thomas, Chess, S., Birch, H.G. et al. Behavioral individuality in early

childhood. New York: New York University Press, 1964.

Winnicott, D.W. The family and individual development. London:

Tavistock Publication, 1965.